Midnight blue sparkles and rhinestones for the party!

Story Department colleagues at Ca del Sole

Bill, Val, me, Margaret, Debbie - together we represent an aggregate couple of centuries of reading!

My purpose in retiring is to spend my days writing full time and traveling full time (with some necessary overlap). There will be books and memoirs, plays and blogs, trips to England and to Italy; and my first step is this blog account. To my delight, the occasion was rousingly celebrated last Friday by a glorious lunch thrown for me at the Ca del Sole restaurant, and all my colleagues attended. I was all decked out in my Chico's Midnight Blue sequin outfit, with Weiss rhinestones for maximum light, bright and sparkling effect!

Pumpkin risotto

Holly and me

Afterwards, I wrote to the Story Department: "I don't think anybody can really grasp what it means to be given a retirement party like that - and mine was one of the thumping greatest I ever heard of - until it happens. There's a reason for ceremonial occasions, and it's hard to convey just what this one meant to me. The fact that you all came! I was truly overwhelmed, and although I'm too hard boiled an old movie biz dame to show much emotion, I felt it. The moment that hit me most was when, at her far end of the table, Teresa said, "You never let us down." I felt I had been handed my gold watch (and I guess I could have literally had one if I'd asked!), and told, "Well done, good and faithful servant." That might sound a bit too Victorian, but honestly, after long and anonymous service done to the best of one's ability, to have everyone there like that, showing appreciation in so many ways, was absolutely...well, gratifying is too small a word."

Me and boss lady Teresa

So, illustrated with pictures from the party, I thought I'd share the Retirement Speech I gave. The talk was adapted from one I've given at Oxford several times, though my own colleagues had never heard it before; I cut out the bits about how to do story analysis and how to sell books to movies, because they didn't need to hear that! Without further ado, here's the talk, entitled:

A Life in the Story Department.

How and why did I become a story analyst? It all goes back

to my grandmother, who was story editor of Universal Studios in 1924. When

writing her biography, one of the things I learned is that despite all the

technological changes that have happened, life in story departments has

remained recognizably the same for at least three quarters of a century.

My grandmother Winnifred Eaton, 1903

My grandmother, Winnifred Eaton, born in 1875, was the first

Asian American novelist. She was one of a family of fourteen “half-caste”

children of an English father and his Chinese wife. Her father Edward Eaton was

an artist whose family, silk merchants, sent him to the Orient on business in

1860. On board ship he met a Chinese girl, Grace Trefusius, and married her.

Grace had been born in Shanghai, but was sold into slavery as a small child to

perform as a circus artist all across Europe. Rescued by an English missionary

she was taken to London and educated to be a missionary herself. Instead, her

husband brought her home and paraded her through the streets of Macclesfield in

Chinese robes crying “Behold my Chinese bride!” This story was used in a famous

novel, JAVA HEAD, in 1918, and twice made into a movie.

The Chinese bride did not go over well in Victorian

Macclesfield, so the young couple emigrated to Montreal, where they raised

their large family in poverty. Two of the girls, Winnifred and her oldest

sister Edith, were ambitious to be writers, and Edith became known as the

godmother of Asian American fiction, under the pen name Sui Sin Far. She’s

considered the “good sister,” and my grandmother, Winnie, is by default the bad

sister. Winnie’s aspirations were commercial; in fact, the first words of the

very first story she ever had published at the age of 14, were “Since I was

first able to think, I have had intense longings for wealth.” She left Montreal

at 20 to become a girl journalist in Jamaica, and from there made her way to

New York where she took on a fake ethnicity (more than a century before Rachel

Dolezol). It was more fashionable to be Japanese than Chinese, so Winnie called

herself Onoto Watanna, and swanned around in kimonos to publicize her 15 pseudo-Japanese

romance novels with titles like The Heart of Hyacinth. The most successful,

A Japanese Nightingale, sold 200,000 copies in 1901 and was made into a

Broadway play and a silent film. Winnie married an alcoholic journalist and was

the sole support of her family, churning out a “book and a baby a year.”

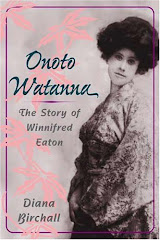

Winnie as "Onoto Watanna" - my book cover

A chameleon who reinvented herself whenever things got rough,

she went to Reno to divorce her husband, and met her second husband there. They

went to Calgary to try ranching, but when that failed she returned to New York

and got the job at Universal; she was the protégé of Carl Laemmle, who sent her

to run the West Coast story department. Another woman writer was fired to make

room for her, and 75 years later I read this woman’s autobiography for work,

and found it contained a vindictive diatribe against my grandmother. The writer

was still alive at the age of 100 and I called her in the nursing home. She

still hated Winnie, and exclaimed “that woman destroyed the story department in

6 months!” But that was all I could get out of her.

Winnie arrived in Hollywood in the days of the silent

5-reelers, and her time there coincided with the transition to talkies. She

worked like a dog, turning out hundreds of scripts and treatments, and she is

credited as screenwriter on six films, including SHANGHAI LADY, EAST IS WEST

and MISSISSIPPI GAMBLER with Edward G. Robinson. She was the first Asian

American woman to work as a screenwriter in Hollywood, but by now she was done

being Japanese. Even though she dressed in white lady business costume, was mostly assigned to write scripts with

exotic themes, about Gypsies, French people, and Chinese cooks. But she worked

on more mainstream scripts as well, such as early versions of BARBARY COAST,

SHOWBOAT, and EAST OF BORNEO (an early KING KONG called OURANG). Her papers are

all held in the University of Calgary library, and it was fascinating for me,

as a story analyst, to read my own grandmother’s screenplays. It was like a

time capsule, and surprising to see how her memos (mostly asking for more

money) and script synopses could have been written today. The process of

reading and passing on screenplays was virtually identical.

1985 Hollywood. Working with Cloe Mayes at MGM!

Winnie had to fight to stay employed in Hollywood, and lost

the struggle at a time when the women who wrote the silent films were losing

their jobs to the men who wrote the talkies. To supplement her income she wrote

for movie magazines. In one piece called “Movie Relatives,” she vented about

people who got jobs through nepotism. In another article, “Butchering Brains:

An Author in Hollywood is as a Lamb to the Slaughter,” she described the

experiences of authors who came to Hollywood in the Eminent Authors Program

started by Samuel Goldwyn. Winnie wrote, “He sits in his office and scans, with

bulging eyes, his first assignment. He is presently either convulsed with mirth

or is stricken dumb with incoherent wrath. He has been assigned to adapt and

treat an “original” by one Suzy Swipes or Davy Jones of Hollywood. It is an

amazing, an incredible document. Its language is almost beyond credence. It is

a nightmare patchwork that contains incidents and characters and gags and plots

of a hundred or more stories that are horribly reminiscent to the Eminent

Author.”

So, things haven’t changed much! As for Winnie, her

estranged husband in Calgary struck oil and became a millionaire; he also took

a mistress, and came to Hollywood to ask Winnie for a divorce. So, at the age

of 56, she seduced him back, and vanquished the mistress. She returned to Calgary,

and lived out the rest of her life as a white Canadian housewife. During World

War II, she’d talk about “the dirty Japs,” just as if she had never pretended

to be Japanese at all.

Her son, my father Paul Eaton Reeve, was a dissolute

Greenwich Village poet, but when he was in Hollywood as a young man his mother

got him work as a reader at MGM. My own son Paul, before he became a librarian,

was a story analyst at Columbia. I believe we are unique as the only family in

which four generations have worked in movie studio story departments. I grew up

in New York with my mother’s family who told me nothing about my flamboyant

grandmother; I had one of her books, a Canadian Western called Cattle which

seemed to be mostly about rape. I suppose this is how I got the idea be a

writer. After college, in the early 1970s, I moved out here, a single mother

with a small child, and had to find work. My aunt recommended that I look up

Winnie’s old literary agent, Ben Medford. He was old style Hollywood, a little

red haired man with a bow tie, who gave me scripts to read in exchange for

lunch. My career began - as now it is ending, appropriately, at lunch.

To get my first job I went through the Yellow Pages, and

called up a list of about 25 literary agencies, production companies and so on.

The H.N. Swanson agency said they needed a receptionist who could read scripts.

Their office was unchanged from the 1920s, like something out of a Raymond

Chandler novel, wood paneled walls with an enormous bluefish trophy, and a

library full of books by clients. I remember finding an early draft of Catcher

in the Rye there. A few years ago I rediscovered my old boss, Ben Kamsler,

another 100-year-old person; still sharp as a tack and reading the trade papers.

I told him it was wonderful to meet somebody 40 years older than me who was

still active, and he immediately retorted, “I hope you don’t tell Warners your

true age!” He was still being bombarded with screenplays himself.

I worked for “Swanie” for about a year, and one day a girl

my own age came into the office. She was Story Editor at Tomorrow

Entertainment, and I thought, gee, why can’t I have a job like that? So I

approached her for a job and she hired me as her reader. I worked for her for a

couple of years; her name was Marcy Carsey, who later went on to become one of

the most successful women in television. When she went to ABC she got me an

interview as program director. I was a story editor briefly but I realized that

these “career” industry jobs were not what I wanted. What I wanted was to stay

home and write, and sleep late. So that’s exactly what I did. First working at

Orion Pictures for Mike Medavoy for about five years, then The Ladd Company for

Laddie and John Goldwyn, for another five years; then John took me to MGM. When

MGM folded John said it would take him about a month to get me over to

Paramount, but I took a more immediate offer from John Schimmel, here. That was

in 1991, and you know the rest of the story.

It was Raymond Chandler who said, “A good script is as rare

as a virgin in Hollywood.” In my first days reading screenplays, I read some great

ones, like CARRINGTON, and AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON. I thought reading

screenplays was all going to be like that, but that’s beginner’s luck! Over the

years I was the first reader on scripts such as ROCKY, TERMINATOR, BLADE

RUNNER, THE RIGHT STUFF, MOONSTRUCK. Later at Warner Bros, I became the “book

person,” specializing in novels, which fulfilled my idea that reading always

seemed the perfect way to earn a living.

Until just about a year ago I would still get a little

frisson of excitement with every new manuscript I was sent. Only when I started

to look at them with a shade of reluctance instead of eagerness, and started

buying rhinestone necklaces and Kate Spade handbags on eBay every two hundred

pages to spur me through my night long tasks, did I realize it was time to stop!

But it took 43 years to get to that point (24 at Warners), so that was pretty

good going. I used to call the job my writing scholarship, for it trained me in

the craft of writing and the discipline of deadlines. It was productive, it was

pleasurable, and I am very grateful to have had what I consider the most wonderful

working life imaginable. And now I can devote myself fully to the work that is

my own.