Light, Bright, and Sparkling has never been a book blog, as my day job is so close to book blogging that writing book reviews after my week's work is done is far too close to a Busman's (or Bookman's) Holiday. But it's hard to resist telling about any especially interesting book I read, and I'm inspired by this wonderful new book from Canada, Early Voices: Portraits of Canada by Women Writers, 1639-1914 (Dundurn Press) edited by Mary Alice Downie and Barbara Robertson, with Elizabeth Jane Errington.

Baroness von Riedesel and her children

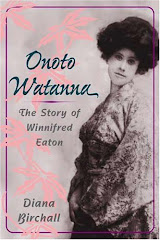

Having an interest in pioneers and frontier life, in the beauty and history of Canada, and in women's lives, for me this book came together as nothing less than a brilliant evocation and illustration of all three. There are of course many anthologies of women writers, Canadian and others, but what makes this one so satisfactory is the exceptionally judicious, felicitous, happy selection. Not growing up or being educated in Canada, one learns shamefully little about Canadian history or literature in school, and I only developed an interest because my grandmother and great-aunt both happened to be pioneering Canadian women authors. My grandmother, Winnifred Eaton (1875-1954) was the first Asian American woman novelist, though she took on a fake Japanese identity and pen name (Onoto Watanna) to write her romantic novels with Japanese settings and titles such as The Heart of Hyacinth and The Wooing of Wisteria. She also wrote two memoir style novels of her early life in Montreal, Me (1915, republished by U. of Mississippi Press) and Marion (1916, reprint forthcoming from U of McGill Press), and two novels of Calgary prairie life in the period between the two world wars, Cattle and His Royal Nibs. Her career was flamboyant and fascinating, and the greatest professional joy of my life was researching and learning about her, and publishing my biography Onoto Watanna (U of Illinois Press, 2001). But even my partisan delight in my fabulous granny cannot blind me to the fact that her older sister, Edith Eaton, is generally seen as the more noble character and arguably finer writer. Both sisters were among the fourteen children of an Englishman and his Chinese wife, and sensitive, idealistic Edith was very sympathetic to her mother's plight as a scorned ethnic minority. Both sisters suffered from prejudice as being "half-caste," but where "Winnie" took the veiled method of creating some sympathetic Asian heroines, Edith fought for justice and equality for the Chinese community in her writing, her journalism, and her social work. Writing under a Chinese pen name, Sui Sin Far, she is now called "the spiritual foremother of contemporary Eurasian authors."

Sui Sin Far, my great-aunt

What ancestors for a nice Jewish girl to have, and I am inordinately proud of them! It was Sui Sin Far's inclusion in this collection that led me to it, but that's not the only, or even the main reason for my very great enjoyment of the book. For that matter, the book is rather cavalier about my grandmother ("We regard the discovery of half-Chinese Sui Sin Far, also known as Edith Maude Eaton, as a triumph. The novelist and journalist, Onoto Watanna, looked promising, until we discovered that she was Sui Sin Far's sister Winnifred, masquerading as an exotic half-Japanese"). No, it is because it serves an introductory purpose better than I have ever seen any related anthology do. As a non-Canadian, I had heard of a few of these women authors, and had even read the books of arguably the most famous, Catherine Parr Traill. I wanted to know more of these remarkable early-Canadian stories, but most selections give you only a thumbnail, so you're left not really "knowing" the author. Or else they give you dull excerpts, so you don't want to know more about the author! Not so here. Each of these excerpts is vital and alive, intensely vivid journalistic prose, that has a "you are there" effect of putting you in the picture. You start reading and the modern world disappears, and you're back in 19th century Canada, with refined and educated women who have been put down almost in the middle of nowhere, and who respond in a variety of fascinating ways. You could seek out and read the full versions of these women's writings, and I have no doubt that I will, but this book also feels quite complete in itself. The selections are so inspired that the reader becomes absolutely rapt in the stories, and when you lift up your head and close the book, you find that you really have learned a great deal! To paraphrase Mr. Eliott in Persuasion on his idea of good company, "that is not a good book, that is the best."

Anna Brownell Jameson

And who are these women? They are nothing if not diverse. The editors have not chosen a group who all sound the same, a collection of Catherine Parr Traill clones, but women of different backgrounds who had very different experiences in early Canada. Elizabeth Jane Errington writes, "We still tend to see New France, British North America, and 19th century Canada as worlds inhabited by strong men and silent women." Nothing could be farther from the case than this eclectic collection, in which we find such voices of vitality.

There's Mary Barbara Fisher (1749 - 1841) whose husband fought in the American Revolution, and as Loyalists they fled to Nova Scotia. A manuscript by her daughter details the settlers' first cruel winter and shows a certain anti-American animosity, for she writes, "There were no domestic animals in our settlement at first except one black and white cat, which was a great pet. Some wicked fellows, who came from the States, killed, roasted and ate the cat, to our great indignation." This depredation seems less horrific when you read the account of how stunningly little the settlers had to eat!

I liked the description by Baroness von Riedesel (1746-1808), wife of the general in command of the Hessian troops, of an 18th century freezer:

"At the beginning of November people lay in their winter provisions. I was very surprised when people asked me how much fowl, and particularly how many fish I wanted and where I should like to have the latter left, since I had no pond. In the attic, I was told, where they would keep better than in the cellars. Accordingly I took three to four hundred, which kept very well through the winter. All that had to be done when a person wanted meat, fish, eggs, apples, and lemons for the midday meal was to put them in cold water the day before. Thus the frost is thoroughly removed, and such meat or fish is just as juicy, even more tender than that we have at home. In addition to this, poultry is packed in snow, which forms such a crust of ice that one must chop away with a hatchet."

A little later the Baroness tells a story of some Indians who kept coming to a settler named Johnson saying they dreamed he gave them rum and tobacco. He gave them all they wanted, but one day went to them and said he dreamed they gave him a certain large piece of land. They held council and told him, "Brother Johnson, we give you the piece of land, but dream no more."

Baroness von Riedesel

Anna Brownell Jameson (1794-1860) the Irish-born wife of the Attorney General of Upper Canada, left him and returned to England where she became a critic and champion of women's rights, but her Winter Studies and Summer Rambles (1838) seems to be a charming account, in which she tells of a tempestuous, wet night spent on a rock in Lake Huron. Later, reaching an inn in Toronto, she rejoiced in a luxurious little bedroom with white curtains, but adds, "but nine nights passed in the open air, or on rocks, and on boards, had spoiled me for the comforts of civilization, and to sleep on a bed was impossible: I was smothered, I was suffocated, and altogether wretched and fevered; I sighed for my rock on Lake Huron."

Indian lodges sketched by Anna Jameson, 1837

Toronto Harbour sketched by Anna Jameson, 1820

It is Anne Langton, from an educated family connected to the Brontes and the Stricklands, who perhaps most graphically details the constant chores of pioneer life. She ran the first school and circulating library in Upper Canada, but after being delivered a load of tallow that she (already with a great deal of work on hand) must form into candles, admits, "I have sometimes thought, and I may as well say it, now that it is grumbling day - woman is a bit of a slave in this country."

Anne Langton

I will tell some more about this fabulous collection of women's writings in another post, but in the meantime, suffice it to say, that if you are inclined to read one book about women writers in Canada: this is the one.

1 comment:

Hi Diana,

This is really fascinating! I am an English teacher from Beijing Foreign Studies University. It was in 2009 that I first came to know Sui Sin Far. I was a visiting fellow at Yale University back then and audited a course called "Asian American women and gender history". That's when I first read your great-aunt's "Mrs. Spring Fragrance" and a couple of other pieces. I was instantly fascinated by her writing and the experience she described in her writing. Right now I, together with a few colleagues of mine, am compiling a "Selected Reading Coursebook of American Literature", and I decide to include Mrs. Spring Fragrance in the book. I was googling for some pictures of Sui Sin Far (painstakingly, actually, as google search has been shamefully censored by our government, and it's almost next to impossible to get something from it without "hopping the 'Great Wall' via some special software I purchased in the US.), and bang, I found your blog, and to my great excitement and thrill, I was reading the blog of Sui Sin Far's grand-niece!!! What are the chances! I did read a bit about your grandmother, and not any of her writing. Anyway, I am writing just to express my admiration to your grandmother and grand-aunt, and hopefully I can get a reply from you, and can include you in the next paper I publish about your grandmother and grandaunt. If you happen to see my note and have the interest in what I am doing, please do drop me an email at zhangweijunn@gmail.com.

Yours sincerely,

Weijun Zhang

Post a Comment