A few years ago, a professor friend mentioned reading about Mark Twain's fabulous gala 70th birthday party at Delmonico's, which was attended by the leading literary lights of the day. The article was in Harper's Weekly for December 23, 1905, and I was all agog because I knew that my novelist grandmother Onoto Watanna was present, along with her friend Jean Webster, a great-niece of Twain (and author of Daddy-Long-Legs). Photographs were taken of each table, and I was delighted to obtain scans of the pictures through the good offices of my friend Peter Hanff and Bob Hirst of the Bancroft Library at Berkeley. I immediately began Googling the guests, and made some surprising discoveries. Later, I was fortunate to score a copy of Harpers myself, on eBay. Now it has belatedly occurred to me that my blog is an ideal format to show some of these pictures, tell about these literary celebrities, and in general try to recreate a magical evening at Delmonico's, over a century ago.

Mark Twain at his birthday dinner

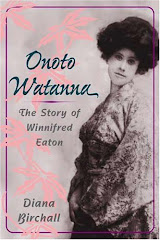

Mark Twain's Bust

Of course I was most eager to see the picture of my grandmother. I longed to know if she wore Edwardian dress like the other ladies, or a kimono? For Onoto Watanna is considered the first Asian American novelist, but she was born Winnifred Eaton (1875 - 1954) and was raised in an entirely English-speaking home in Montreal. Her father was an English painter, Edward Eaton, her mother Grace Trefusius was Chinese but had been educated in England, as a missionary. They had 14 "half-caste" children, and the oldest daughter, Edith (1865 - 1914), was also a writer. Together they are known as the "Eaton sisters," but Edith, who used the pen name Sui Sin Far and wrote stories of the immigrant Chinese, is held in high critical and social esteem, as the godmother of Asian American fiction. Winnifred, or Winnie, sought a frankly commercial career, and took on a fake "Japanese" identity, the better to publicize her fashionable pseudo-Japanese romances. She was a mistress of publicity, a poseur who changed her ethnic identity as it suited her.

Here is Winnie at her table, in conventional Western costume, the lady at the center of the picture:

Onoto Watanna (Winnifred Eaton), center; Gelett Burgess beside her. (Click on pictures to see larger)

Turning my attention to the others at her table, I was amazed and charmed to notice that she was sitting right next to Gelett Burgess. He was the author of Goops and How to Be Them, then still a fairly new book (1900) as well as the immortal verse:

I never saw a purple cow

I never hope to see one;

But I can tell you, anyhow,

I'd rather see than be one!

Original Purple Cow illustration, 1895

What can the dinner table conversation have been like? I imagine they didn't talk too much, judging by the length and number of the tribute speeches printed in Harpers. Winnie evidently came to the party unaccompanied; her hard-drinking newspaper reporter husband Bertrand Babcock was not present, but clearly nothing would have kept her away from the occasion - as evidenced by the fact that she was actually nine months pregnant with her third child (my Aunt Doris)! In the picture, she manages to conceal this with some dexterity, slumping down so that only her head and shoulders are in view. Yet she appears to be quite enjoying herself, and unless it is my imagination, she and Burgess have a sort of subtle conspiratorial look together. He was of course one of the funniest men of the era, brilliantly playful with words, though I should have thought it daunting to eat in company with a man who wrote:

The Goops they lick their fingers

And the Goops they lick their knives

They spill their broth on the tablecloth -

Oh, they lead disgusting lives!

The Goops they talk while eating,

And loud and fast they chew

And that is why I'm glad that I

Am not a Goop - are you?

The New York Times gives a delightful description of the dinner at Delmonico's:

"The dinner began at 8 o'clock. Soon before that hour the guests began to gather in the parlor adjoining the Red Room. In the corridor outside, place had been prepared for an orchestra of forty directed by Nahan Franko. When the march, serving as a signal for the procession to the dining room, was played, Mr. Clemens led the way, with Mrs. Mary E. Wilkins Freeman on his arm. The couples that followed would have attracted attention wherever they were seen and recognized. Col. Harvey led Princess Troubetzkoy, who once was Amelia Rives and still writes under that name. Andrew Carnegie and Agnes Repplier, the essayist, followed side by side. After them came John Burroughs and Mrs. Louise Chandler Moulton, who was the first author from whom Henry Mills Alden received a contribution after becoming editor of Harper's Monthly, more than forty years ago. The Rev. Dr. Henry Van Dyke escorted Mrs. Frances Hodgson Burnett, while Bliss Carman, the poet, led Mrs. Ruth McEnery Stuart. While the dinner was in progress the guests - one table at a time - went out into another room and had their pictures taken in groups. The pictures will form the most conspicuous feature of an album which is to be given to Mr. Clemens as a souvenir of the occasion."

Delmonico's was then in its heyday, the luxurious eatery where Diamond Jim Brady and Lillian Russell held court, where Lobster Newberg and Oysters Rockefeller were invented, where the rich and famous generally enjoyed the high life. This was definitely an occasion I'd like to travel back in time to attend!

An artist's rendition of the occasion

And now comes the luxury of speculation. Who are all these people and how did they happen to be seated as they were? As the New York Times put it:

"...his friends and fellow-craftsmen in literature gathered in the Red Room at Delmonico's for the celebration. Barring a half dozen or so, all were guaranteed to be genuine creators of imaginative writings--or illustrators of such writings. The guarantee was furnished by Col. George Harvey, editor of The North American Review, who was the host of the evening as well as the Chairman."

Funny, isn't it, how all the notable literati of an era are but passing shadows - who knows all these names now? Only scholars. Some were nearing the end of their fame, others were still so early in their careers that you wonder how they got invited. Winnie was at the apogee of hers, for her best selling novel A Japanese Nightingale had sold 200,000 copies in 1901 (a copy is in Mark Twain's library; the house site indicates that it is one of the last books that his wife Livy read), and the previous year (1904) was made into a Broadway play, which flopped: a review said it the play died "like a poor little bird that had twisted its larynx." At this stage of her life Winnie was doing what she called turning out "a book and a baby a year." There she sits, demure, age 30, looking very pretty and concealing her pregnancy in her elegant Edwardian dress, her dark hair piled and rolled high, at a table of people who all look rather ineffably stiff and bored and as if they don't have a lot in common. Yet I like to think Winnie was well entertained by Burgess; at any rate, she looks as if she were.

Winnie, 1903

The other man at her table, Edwin Lefevre, is the author of Reminiscences of a Stock Operator - which is one of my husband Peter's favorite books. Imagine her sitting there with him and Goops! (I do hope they didn't lick their fingers).

The other two ladies at the table are Famous Poetesses. Josephine Daskam Bacon was a children's writer (Memoirs of a Baby) now remembered for writing the Girl Scout Handbook, but Alice Duer Miller is especially fascinating. Exactly Winnie's age, dark and beautiful, she was from a far loftier background than my raffish grandmother. Her family was wealthy, with a prominent history going back to the Revolutionary War; she was educated at Barnard and at the time of this party was already known as a poetess, though the most interesting part of her career was still to come. She became a famous Suffragette, author of the satirical Suffrage movement poem "Are Women People?" but her greatest popular success was with her verse novel "The White Cliffs" (1940). This was about an American girl who marries an English aristocrat, and brings up his son in England after her husband is killed in World War I. It ends with the lines:

I am American bred

I have seen much to hate here - much to forgive,

But in a world in which England is finished and dead,

I do not wish to live.

Alice Duer Miller

The most exciting years of the Suffragette movement, World War II, and so much else, was still in the unknown future when these writers sat down in Delmonico's to honor Mark Twain, who was then four years away from his death. The speech he gave on this occasion can be read here:

http://www.pbs.org/marktwain/learnmore/writings_seventieth.html

More on the glittering guests in my next post...

To Be Continued