The Austen Variations collection Persuasions Behind the Scenes is now available for FREE, at all major booksellers. I have several "scenes that Austen never wrote" in this volume, and here's one of my favorites, a conversation between Sir Walter Elliot and his daughter Elizabeth, called "Can We Retrench?"

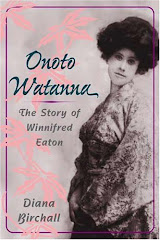

Can We Retrench? by Diana Birchall

"It had not been possible for him to spend less: he had done

nothing but what Sir Walter Elliot was imperiously called on to do; but

blameless as he was, he was not only growing dreadfully in debt, but was

hearing of it so often, that it became vain to attempt concealing it longer,

even partially, from his daughter. He had given her some hints of it the last

spring in town; he had gone so far even as to say, "Can we retrench? does

it occur to you that there is any one article in which we can retrench?" (Persuasion, Jane Austen)

“Papa,” said Elizabeth Elliot to Sir Walter,

“I must have some new gowns.”

It had been a busy day, as all London days

were, when father and daughter were up for the Season. Expensive dinners were

given and taken; engagements at Court enjoyed; and in the afternoons Sir Walter

liked to saunter over to the House of Commons with his handsome daughter, or

for an airing to see and be seen in the chaise and four. Today he had been

hobnobbing with some cronies at his Club while Elizabeth went shopping for

various female articles.

Now they were home, to dine by themselves

before spending the evening at a dance at Almack’s. Sir Walter looked up from

his chop. “I think you are right, my dear,” he answered. “I have noticed you

not looking quite the thing.”

“Why, Papa, I hope you do not think me

faded!” Elizabeth exclaimed.

“No, no. To be sure not. You are as blooming

as ever, certainly. But your gowns – I was noticing, yesterday when we were

paying calls, that some of the ladies’ costumes seemed superior. That primrose day

dress with the streamers Lady Beresford wore, became her very well I thought.

That muslin of yours looked a bit limp beside it.”

“Oh, I know, Papa,” Elizabeth almost wailed,

“I looked a perfect fright.”

Sir Walter frowned. “Not that, I hope,” he

said gravely, “but it is not often you make such a poor show. What in heaven’s

name induced you to wear such a plain dress? And – and, when we went to the

opera, your cloak – “

Their eyes met. “It has holes in it,”

Elizabeth said grimly, “and Sally has not been able to repair it properly. She

has not the skill.”

Sir Walter looked discomfited. “Well,” he

said at last, “you have made your point. You do need a new wardrobe. Why did

not you have some new things made before we came to London?”

Elizabeth averted her gaze, and reddened.

“The dressmaker’s bill,” she muttered.

“Oh, I see.” He made a face. “Those small

market town dressmakers, what a pother they get into about the least thing.”

“She has not been paid in three years.”

“Ah. Well, she should consider it an honour

to be allowed to dress you at all! She can make a good deal of money merely by

being known as dressmaker to Miss Elizabeth Elliot of Kellynch-Hall, you know.”

“She doesn’t see it that way,” sighed

Elizabeth, “and – and she told me to take my business elsewhere.”

“What insolence! But then, why did you not

get some pretty things when we came to Town? There is a Miss Bell, I know, whom

all the ladies speak of as so clever. Did she not make Mrs. Harrison’s latest ensemble

– that lemon-coloured Russian velvet gown?”

Elizabeth was dabbing at her eyes now. “Yes,”

she sobbed. “Miss Bell is all the mode, but when I went to see her about a

spring wardrobe, she told me – she told me that she would not dress me,

because,” she burst out with it, “my credit was not good!”

Sir Walter pushed aside his dinner and rose

to his feet. “She dared! A mere tradeswoman! And for her to turn you away, an

Elliot of Kellynch-Hall, when you owe her nothing!”

“Not quite that, Papa,” Elizabeth managed to

say.

“What do you mean?”

“Don’t you remember, she did make some things for me last year – the spotted sarsanet that every body thought was so pretty, and, and the cloth-of-silver pelisse? And – “

“Don’t you remember, she did make some things for me last year – the spotted sarsanet that every body thought was so pretty, and, and the cloth-of-silver pelisse? And – “

“Go on.”

“And we did not pay her.” Elizabeth hung her

head, looking down at her plate.

There was a silence, and all Sir Walter could

find to say was a half-hearted, “I do not know what has become of trades people

these days. No proper respect to a gentleman’s family.”

Father and daughter looked at each other

despondently. “I have lost my appetite,” sighed Sir Walter.

“So have I.”

“Come then, let us sit and have a look at the

Baronetage. That always makes us feel better, does it not? We can compare how

much newer the other creations are than our own ancient family…”

At that moment a loud knock at the door was

followed by running footsteps. Father and daughter started, as the housemaid,

Letty, entered breathlessly, with a man hard on her heels, who pushed his way

past her.

“Letty! What is the meaning of this!”

“He would come in, Sir, I could not stop him

– “

“To what do we owe this unwarrantable

intrusion,” thundered Sir Walter, looking disdainfully at the stranger, who

appeared to be a stout man of business in middle life.

“Harold Cadgwith, sir, of Gudgeon and

Cadgwith. The banking concern. You owe us a note, you do, for eight hundred

pounds, eighty and sixpence.”

“The impertinence of you! Get out of here at

once!”

“Begging your pardon, sir, but I won’t. Not

until you have paid me or issued a promissory note from another account. I can

call the constable, and have you hauled before the magistrate. This debt has

been running for eighteen months, and my bank won’t have it. You’ll go to

debtor’s prison if you don’t settle this, lordship or not.”

Sir Walter was shaken, but did not lose his

composure. He withdrew a card from his breast and held it out with such an

elegant air that the man took it, wordlessly.

“That is the direction of my man of business,

John Shepherd,” he said in as lordly a tone as if Cadgwith had been the debtor,

not himself. “I will write to him tonight, and order him to settle with you.

You have my word of honour as a gentleman. Now kindly withdraw.”

“I’ll go,” said Cadgwith, “I’m going. I’m

going to see this Shepherd, that’s what, and for all your fine airs, your

lordship, it’s gaol for you if your word’s no good, certain sure.” He strode

out and Sir Walter sank into a chair, his head in his hands.

Elizabeth was white with shock and horror.

Eventually, her father rose and shuffled over to his writing-desk, unlocked it,

and pulled out a terrible mass of bills, dunning-notices, and cancelled

accounts. He stirred the heap of papers uncomprehendingly. At last he looked up

at his daughter, who stood beside him, unable to speak.

“Elizabeth,” he said, “can you think of any

way in which we might retrench?”

*****************

If you enjoy reading Persuasion variations, you can enjoy a whole book of them for free! Here's the Amazon link:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07NLMK3HV?pf_rd_p=ab873d20-a0ca-439b-ac45-cd78f07a84d8&pf_rd_r=1RJQHVQ0N4GSYZVYSR3V